As the carbon market explodes in value, many are starting to wonder: who is benefitting? From 2020 to 2021 alone, the voluntary market quadrupled in value to $2 billion. Much of this value was created by local communities implementing climate solutions on the ground, but how much value returns to them? How much value should return to them? What does that value look like? These questions sit at the heart of benefit sharing discussions.

Benefit sharing is becoming a growing part of the carbon community’s rhetoric. However, it often swings from being overcomplicated to oversimplified, both of which often result in equally ineffective outcomes. While we at Taking Root do not claim to have all the answers, we would like to share some thoughts and insights from our years of experience working with smallholders in forest carbon. We hope that it can spur further discussions on how carbon forces us to think about livelihoods.

Let’s align on what benefit sharing means

Broadly speaking, benefit sharing refers to how the value (i.e., benefit) created from the sale of carbon credits is distributed (i.e., sharing). Typically, it focuses on how value is distributed to communities–the ones implementing climate solutions on the ground. Depending on the carbon project, this could be any number of stakeholders: smallholder farmers growing trees, indigenous groups conserving forests, or community groups restoring grasslands. For the sake of this article, when we say ‘communities’, we are referring to smallholder farmers growing trees.

Who exactly is sharing the benefits?

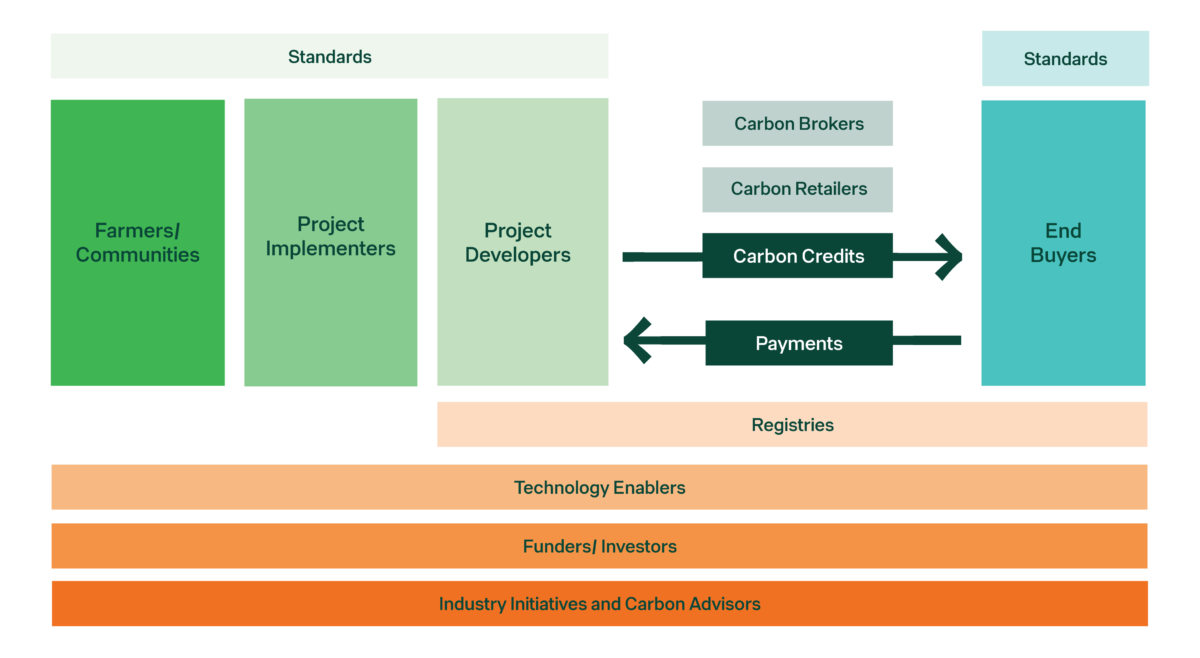

Carbon markets started as an exchange between two actors: corporates and project developers. As the market expanded, a flood of new actor types entered the market. This has made benefit sharing increasingly complex when it comes to ensuring value gets back to communities on the ground.

When a company purchases a carbon credit, the value from that sale can be shared between farmer, project implementer, project developer, project certifier, technology enabler, carbon retailer, carbon broker, investors, and speculators, to name a few. The specific mix of actors will differ depending on the type of carbon project and its needs.

Many have started to question if there are more actors than what is needed. This is a concern because if there is a surplus of actors, value is detracted from communities on the ground. However, there are justified reasons for so many having entered the market.

As the market has grown, so has its needs. Carbon standards emerged to certify that a carbon credit has real climate benefit. Carbon retailers alleviated sales burden off of project developers so that developers can focus on creating impact. Investors are funding the capital-intensive process of creating new projects. The sophistication of the carbon market is both accelerating and safeguarding impact.

The challenge with the market sophisticating so quickly is that it is often hard to tell if with the addition of all these actors, equitable outcomes are being produced for communities. New market entrants may or may not have the knowledge about what those outcomes should be, have the tools to create those outcomes, or even value those outcomes at all.

With that in mind, there are several lessons that Taking Root has learned through our experience to ensure that benefit sharing is conducted in an equitable way. Here are some of the key considerations for equitable benefit sharing.

Key considerations for equitable benefit sharing

1. Ensure sufficient value to communities so that engaging in a carbon activity is worth it.

The most important consideration for any project is to ensure that it is worth it for a community to engage in a carbon activity. This is fundamental for any project to succeed. Take smallholder farmers in reforestation. If farmers can’t improve their livelihood by growing trees, why would they choose to grow trees in the first place?

At a minimum, the price of carbon needs to cover these base costs. Not doing so not only creates risk for projects, but also creates inequitable outcomes for communities.

2. Ensure market premiums are shared with communities.

Once a baseline has been established for value needing be shared with communities, then look at market premiums. Is the market offering more value than the established baseline? If yes, then ensure that communities are benefitting from those premiums.

There are a few ways to safeguard for this. The first is to ensure that a percentage of the sale of carbon credits always goes to communities. That way, if market prices of carbon increase, communities will benefit proportionately.

The second way is to mitigate additional resale transactions that don’t benefit communities. This is of particular concern in the secondary market. When carbon credits are traded with multiple transactions, it is challenging to ensure that communities retain value with each transaction. Until proper mechanisms can be built that allow communities to benefit from each transaction, the secondary market should be approached with caution.

3. Quality comes with a cost.

More and more players are entering the market, each with their own value proposition. Carbon advisors and ratings agencies are making it easier for buyers to evaluate project quality. Technology enablers are making it easier for project developers to manage and monitor their projects. As more organizations look to play supporting roles in the market, we can categorize them into two broad types:

- Those who increase the ease and quality of project development (e.g., technology enablers, carbon retailers)

- Those who provide assurance to buyers of the quality for the credits they are purchasing (e.g., ratings agencies)

Actors in each one of these categories undoubtedly can provide value. They are entering the market as a response to the demand for better quality. But improving project quality means creating additional work for projects, which comes with a cost.

The demand for quality should not come at the expense of communities. With costs rising, prices cannot remain the same. As buyers increasingly expect projects to respond to quality demands through enhanced processes, reporting, and verification, they must be willing to pay for this added value. That way, they ensure that communities also benefit when additional service providers support the project.

4. There is no one-size-fits-all approach.

Projects are set up in a diverse number of ways. Some project developers work with a project implementer who works with communities. Other times, project developers also act as the project implementer, working directly with communities. Some project developers sell directly to end buyers, others work through retailers. Any of these setups can have value and make sense based on the project context.

Besides different actor configurations, there also different project types to consider. Reforestation projects work differently from forest conservation projects. Improved forest management is different from agroforestry.

We need to apply a case-by-case approach to evaluate equitable flows of value to communities. Trying to standardize benefit sharing across all projects will inevitably fail, as too much nuance exists to make this possible.

Benefit sharing going forward

As the carbon market continues to develop, new challenges to benefit sharing will surely emerge. While we have listed some key considerations, it is by no means an exhaustive list. Ultimately, benefit sharing is something that requires ongoing discussion and deliberation.

What is clear is that actors must continually ask themselves: are the outcomes we create fair for those communities? If the market holds itself accountable to this question, then we can make important strides towards ensuring that communities on the ground benefit in a way that is truly equitable.